I found this article on another website and wanted to share it here. It could save a life.

Courtesy: Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills

The Ten Essentials list first appeared in the third edition of Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills, released in 1974 by Mountaineers Books. Freedom, as it is affectionately known, is written entirely by volunteers, and we released the 9th edition in November 2017.

THIS BLOG WAS UPDATED IN FEBRUARY 2018 TO REFLECT OUR MOST UP-TO-DATE LIST OF GEAR ESSENTIALS.

The origin of the Ten Essentials dates back to our climbing courses in the 1930’s, and the purpose has always been to answer two basic questions:

- Can you respond positively to an accident or emergency?

- Can you safely spend a night (or more) outside?

Certain equipment deserves space in every pack. Mountaineers will not need every item on every trip, but essential equipment can be a lifesaver in an emergency. Exactly how much equipment “insurance” should be carried is a matter of healthy debate.

Some respected minimalists argue that weighing down a pack with such items causes people to move slower, making it more likely they will get caught by a storm or nightfall and be forced to bivouac. “Go fast and light. Carry bivy gear, and you will bivy,” they argue. The other side of this debate is that, even without the extra weight of bivy gear, a group may still be forced to bivouac. Each party must determine what will keep them safe.

Most members of The Mountaineers take along carefully selected items to survive the unexpected. Whatever your approach to equipment, a checklist will help you remember what to bring.

Over time, the Ten Essentials list has evolved from a list of individual items to a list of functional systems.

TEN ESSENTIALS: THE CLASSIC LIST

- Map

- Compass

- Sunglasses and sunscreen

- Extra clothing

- Headlamp or flashlight

- First-aid supplies

- Firestarter

- Matches

- Knife

- Extra food

TEN ESSENTIALS: FREEDOM 9 SYSTEMS

- Navigation: Map, altimeter, compass, [GPS device], [PLB or satellite communicators], [extra batteries or battery pack]

- Headlamp: Plus extra batteries

- Sun protection: Sunglasses, sun-protective clothes, and sunscreen

- First aid: Including foot care and insect repellent (if required)

- Knife: Plus repair kit

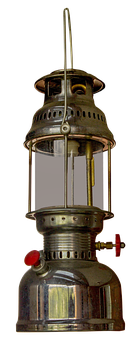

- Fire: Matches, lighter and tinder, or stove as appropriate

- Shelter: Carried at all times (can be light emergency bivy)

- Extra food: Beyond minimum expectation

- Extra water: Beyond minimum expectation, or the means to purify

- Extra clothes: Beyond minimum expectation

The Ten Essentials is a guide that should be tailored to the nature of the trip. Weather, remoteness from help, and complexity should be factored into the selected essentials. The first seven essentials tend to be compact and vary little from trip to trip, and so they can be grouped together to facilitate packing. Add the proper extra food, water, and clothes, and you’re ready to go. This brief list is intended to be easy to remember and serve as a mental pre-trip checklist.

Each essential is discussed in more detail below, as published in Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills, 9th Edition.

1. NAVIGATION

Modern tools have revolutionized backcountry navigation. Today’s mountaineer carries five essential tools while navigating the backcountry: map, altimeter, compass, GPS device, and a personal locator beacon (“PLB”) or other device to contact emergency first responders. Wilderness navigators need to carry these tools and know how to use them – if life is threatened, they need to be able to communicate with emergency responders. Using multiple tools increases confidence in location and route, provides backup when tools fail, and increases situational awareness.

Map. Maps synthesize a vast amount of information about a region that cannot be replicated by written descriptions or memory. Each climber should carry a physical topographic map protected in a case or resealable plastic bag – it is not fragile, needs no electricity, and provides both backup and the “big picture” about a region that cannot be replicated by written descriptions or a tiny screen. If your primary map is a fragile battery-driven electronic device, carry at least one redundant device and backup power, and always carry a printed topographic map as a backup.

Altimeter. Mountaineers have long understood the importance of knowing elevation for navigation. Referring to a topographic map and knowing your elevation solve half of the navigation equation, day or night, clear skies or foggy. With just one more scrap of data – a trail, a stream, a ridge, or a bearing to a known peak – climbers can often determine where they are. Today’s altimeter is a sliver of silicon that can measure air pressure or use GPS satellite signals or a combination of the two. The modern mountaineer tends to use an altimeter more frequently than a compass.

Compass. Robust and easy to use, this essential tool allows wilderness travelers to orient the map and themselves to the landscape. A compass with a baseplate is essential for taking, measuring, and following field bearings and matching them with the map. Many smartphones, GPS devices, and wristwatches also contain electronic compasses.

GPS device. GPS has revolutionized navigation and accurately gives climbers their location on a digital map. Modern phones, combined with a reliable GPS app, rival the best dedicated GPS units for accuracy and are easier to use. Devices often have extensive libraries of maps, many available free; download the ones you need before your trip. Together with downloaded digital maps, phones (or tablets) can guide climbers in the wilderness far from any cell towers. The caveats? Phones are fragile and they need electricity. Climbers should take steps to armor these delicate devices, keep them dry in the rain, and extend their battery life. Bringing a fully charged external battery pack is an important precaution. Dedicated GPS devices are often more rugged and weatherproof than phones, making them a good choice for extreme environments.

PLBs and satellite communicators. Historically, the mountaineer has needed to be completely self-reliant, and climbers should still have that mindset when entering the wilderness today. But when an emergency unfolds despite good tools, preparation, and training, most climbers welcome help. PLBs and satellite communicators determine your position using GPS and then send a message using government or commercial satellite networks. These devices have saved many lives; all backcountry travelers should strongly consider carrying one. Satellite phones are reliable in wilderness, but regular phones, which rely on proximity to cell towers, are not. Unless you are certain you will have a signal, assume that your phone will not function to make calls from the backcountry.

2. HEADLAMP

For climbers, headlamps are the flashlight of choice, freeing the hands for anything from cooking to climbing. Even if the climbing party plans to return before dark, each climber must carry a headlamp and consider carrying a backup. The efficient, bright LED bulb has completely replaced the inefficient incandescent bulb of a few years ago. An LED bulb lasts virtually forever but batteries do not, so carry spares. If you are using a rechargeable headlamp or batteries, start with a full charge. Any headlamp carried by an outdoor shop will be weatherproof, and a few models can survive submersion. All models allow the beam to be tilted down for close-up work, such as cooking, and pointed up for looking in the distance. Some headlamps feature a low-power red LED to preserve night vision and help climbers avoid disturbing tent mates during nocturnal excursions.

3. SUN PROTECTION

Carry and wear sunglasses, sun-protective clothes, and broad-spectrum sunscreen rated at least SPF 30. Not doing so in the short run can lead to sunburn or snow blindness; long-term unpleasantness includes cataracts and skin cancer.

Sunglasses. In alpine country, high-quality sunglasses are critical. The eyes are particularly vulnerable to radiation, and the corneas of unprotected eyes can easily burn before any discomfort is felt, resulting in the excruciatingly painful condition known as snow blindness. Ultraviolet rays penetrate cloud layers, so do not let cloudy conditions fool you into leaving your eyes unprotected. It is advisable to wear sunglasses whenever you are outside and it is bright. This becomes critical on snow, ice, and water and at high altitudes.

Sunglasses should filter at least 99 percent of UV (ultraviolet) light, including both UVA and UVB. (Most opticians can test an old pair if you are unsure.) The tint in sunglasses allows only a fraction of the visible light through the lens to the eyes. Sunglasses, when rated, are usually scored by VLT (visible light transmission), or occasionally by percentage of light blocked. For glacier glasses, a lens should have a VLT rating of 5 to 10 percent. For conditions that don’t involve snow or water, “sports sunglasses” with a VLT rating of 5 to 20 percent are sufficient. Many sunglasses have no VLT rating and should be treated as cornea-scorching fashion accessories. Look in a mirror when trying on sunglasses: if your eyes can easily be seen, the lenses are too light. Lens tints should be gray or brown for the truest color; yellow provides better contrast in overcast or foggy conditions.

Sunglass lenses should be made of polycarbonate or Trivex (a form of polyurethane). Glass, while more scratch-resistant, is heavy and can shatter. High-quality sunglasses can have a variety of helpful coatings including ones that repel water or minimize scratches or fogging. While polarized lenses can decrease glare, they annoyingly black out camera and phone LCD screens in certain orientations. Photochromic lenses automatically adjust to changing light intensity, but most lack a sufficient VLT rating for snow and adjust slowly in cold conditions. Sunglass frames should be a wraparound style or have side shields to reduce the light reaching your eyes, yet allow adequate ventilation to prevent fogging. Problems with fogging can be reduced by using an antifog lens cleaning product.

Groups should carry at least one pair of spare sunglasses in case a party member loses or forgets a pair. Eye protection can be improvised by cutting a bit of mylar from an emergency blanket or making small slits in piece of cardboard or cloth.

Sun-protective clothes. Clothes offer more sun protection than sunscreen. Long underwear or wind garments are frequently worn on sunny glacier climbs. The discomfort of long underwear, even under blazing conditions, is often considered a minor nuisance compared with the hassle of smearing on sunscreen. Some garments are given a UPF (ultraviolet protection factor) rating, a system that is calibrated the same as the SPF rating. A UPF 50–rated garment allows 1/50th of the UV radiation falling on its surface to pass through it. Most clothes do an admirable job blocking UV rays, but don’t expect a thin white t-shirt to protect you on a long glacier climb. For the most part, UPF ratings are not critical except to those with sensitive skin. And whenever possible, wear a hat—preferably one with a full brim.

Sunscreen. Sunscreen is vital to climbers’ well-being in the mountains. Although individuals vary widely in natural pigmentation and the amount of screening their skin requires, the penalty for underestimating the protection needed is severe, including the possibility of skin cancer. Certain diseases, such as lupus, and some medications, such as antibiotics and antihistamines, can cause extra sensitivity to the sun’s rays.

While climbing, use a broad-spectrum sunscreen that blocks both ultraviolet A (UVA) and ultraviolet B (UVB) rays. UVA rays are the primary preventable cause of skin cancer; UVB rays primarily cause sunburn. To protect skin from UVB rays, use a sunscreen with a sunburn protection factor (SPF) of at least 30. If you are near snow or water, use SPF 50 on thin-skinned areas such as the nose and ears.

The EPA highly recommends using sunscreens that carry the regulated term “broad spectrum.” While there is no standard rating for UVA such as SPF, the term “broad spec¬trum” means “that the product provides UVA protection that is proportional to its UVB protection.” Most sunscreen ingredients absorb UV light through a chemical reaction—although titanium dioxide and zinc oxide physically block UV and cause the fewest skin reactions. Of all the chemicals used in sunscreen, these four are most likely to cause adverse skin reactions: aminobenzoic acid (PABA), dioxybenzone, oxybenzone, and sulisobenzone.

All sunscreens are limited by their ability to remain on the skin while you are sweating. US manufacturers can no longer claim that sunscreens are “waterproof” or “sweatproof” or identify their products as “sunblock.” It is feasible for a sunscreen to be water resistant for up to 80 minutes; but regardless of the claims on the label, reapply it frequently. Frequent reapplication is often impractical on a climb, so put on a heavy coating in the morning, wear sun-protective clothes, and reapply when you can.

Generously apply sunscreen to all exposed skin, including the undersides of your chin and nose and the insides of nostrils and ears. Few climbers apply enough – follow the Australian adage “Slop it on!” Even if you are wearing a hat, apply sunscreen to all exposed parts of your face and neck to protect against reflection from snow or water. Apply sunscreen 20 minutes before exposure to the sun, because it usually takes time to start working. Sunscreen that migrates into the eyes from sweat stings relentlessly. Kids’ “no-tear” sunscreen is pH balanced to help prevent this problem and so some climbers only use these products. Lips burn, too, and require protection to prevent peeling and blisters. Reapply lip protection frequently, especially after eating or drinking. When your sunscreen is past the expiration date or more than three years old, replace it.

4. FIRST AID

Carry and know how to use a first-aid kit, but do not let the fact that you have one give you a false sense of security. The best course of action is to always take the steps necessary

to avoid injury or sickness in the first place. Training in wilderness first aid or wilderness first responder skills is worthwhile. Most first-aid training is aimed at situations in urban or industrial settings where trained personnel will respond quickly. In the mountains, trained response may be hours – even days – away.

The first-aid kit should be compact and sturdy, with the contents wrapped in waterproof packaging. Commercial first-aid kits are widely available, though most are inadequate. A basic first-aid kit should include bandages, skin closures, gauze pads and dressings, roller bandage or wrap, tape, antiseptic, blister prevention and treatment supplies, nitrile gloves, tweezers, a needle, nonprescription painkillers and anti-inflammatory, antidiarrheal, and antihistamine tablets, a topical antibiotic, and any important personal prescriptions, including an EpiPen if you are allergic to bee or hornet venom.

Consider the length and nature of each trip in deciding what to add to the basics of the first-aid kit. For a climbing expedition, consider bringing appropriate prescription medicines.

5. KNIFE

Knives are so useful in first aid, food preparation, repairs, and climbing that every party member needs to carry one, preferably with a leash to prevent loss. In addition, a small repair kit can be indispensable. On a short trip, many climbers carry a small multitool, as well as strong tape and a bit of cordage. The list lengthens for more remote trips, and climbers carry an imaginative variety of sup-plies depending on previously experienced – or imagined – calamities. Supplies include other tools (pliers, screwdriver, awl, scissors) that can be part of a knife or pocket tool or can be carried separately – perhaps even as part of a group kit. Other useful repair items are safety pins, needle and thread, wire, duct tape, nylon fabric repair tape, cable ties, plastic buckles, cordage, webbing, and replacement parts for equipment such as a water filter, tent poles, the stove, crampons, snowshoes, and skis.

6. FIRE

Carry the means to start and sustain an emergency fire. Most climbers carry a disposable butane lighter or two instead of matches. Either must be absolutely reliable. Firestarters are indispensable for igniting wet wood quickly to make an emergency campfire. Common useful firestarters include chemical heat tabs, cotton balls soaked in petroleum jelly, and commercially prepared wood soaked in wax or chemicals. Alternatively, on a high-altitude snow or glacier climb where firewood is nonexistent, it is advisable to carry a stove as an additional emergency heat and water source.

7. SHELTER

Carry some sort of emergency shelter (in addition to a rain shell) from rain and wind, such as a plastic tube tent or a jumbo plastic trash bag. Single-use bivy sacks made of heat-reflective polyethylene are an excellent option at less than 4 ounces. “Emergency space blankets,” while cheap and lightweight, are inadequate to the task of keeping out wind, rain, or snow while retaining body heat. A tent can serve as the essential extra shelter only if it stays with the climbing party at all times. A tent left behind in base camp is not enough. Carry an insulated sleeping pad to reduce heat loss while sitting or lying on snow or wet terrain.

Even on day trips, some climbers carry a regular bivy sack as part of their survival gear. A bivy sack at about 1 pound (0.5 kilogram) protects insulating clothing layers from the weather, minimizes the effects of wind, and traps much of the heat escaping from your body inside its cocoon.

8. EXTRA FOOD

For shorter trips, a one-day supply of extra food is a reasonable emergency stockpile in case foul weather, faulty navigation, injury, or other reasons delay a climbing party. An expedition or long trek may require more, and on a cold trip remember that food equals warmth. The food should require no cooking, be easily digestible, and store well for long periods. A combination of jerky, nuts, candy, granola, and dried fruit works well. If a stove is carried, cocoa, dried soup, instant coffee, and tea can be added. Some climbers only half-jokingly point out that exotic flavors of energy bars and US Army meals ready to eat (MREs) serve well as emergency rations because no one is tempted to eat them except in an emergency. And a few packets of instant coffee can help a dedicated coffee drinker keep a clear head.

9. EXTRA WATER

Carry sufficient water and have the skills and tools required to obtain and purify additional water. Always carry at least one water bottle or hydration bag or bladder. Wide-mouth containers are easier to refill. While hydration bladders are designed to be stored in the pack and feature a plastic hose and valve that allow drinking without slowing your pace, they are prone to leaking and freezing, are notoriously hard to keep clean, and often lead climbers to carry more water than they need to.

Before starting on the trail, fill water containers from a reliable source. In most environments, you need to have the ability to treat water – by filtering, using purification chemicals, or boiling – from rivers, streams, lakes, and other sources. In cold environments, you will need a stove, fuel, pot, and lighter to melt snow. Daily water consumption varies greatly. For most people, 1.5 to 3 quarts (approximately the same in liters) of water per day is enough; in hot weather or at high altitudes, 6 quarts may not be enough. Plan for enough water to accommodate additional requirements due to heat, cold, altitude, exertion, or emergency.

10. EXTRA CLOTHES

What extra clothes are necessary for an emergency beyond the basic climbing garments used during the active portion of a climb? The term “extra clothes” refers to additional layers that would be needed to survive the long, inactive hours of an unplanned bivouac. As this question: What extra clothes are needed to survive the night in my emergency shelter in the worst conditions that could realistically be encountered on this trip?

An extra layer of long underwear can add warmth without adding much weight. An extra hat or balaclava will provide more warmth for its weight than any other article of clothing. For your feet, bring an extra pair of heavy socks; for your hands, an extra pair of mittens. For winter and expedition climbing in severe conditions, bring more insulation for your torso as well as legs.

PREPARING FOR THE FREEDOM OF THE HILLS

When you go into the wilderness, you should carry essential gear and leave the rest at home. Achieving that balance takes knowledge and good judgement. Understanding the basics of clothing and equipment will help you decide on those essentials needed to be safe, dry, and comfortable in the mountains.

.png)

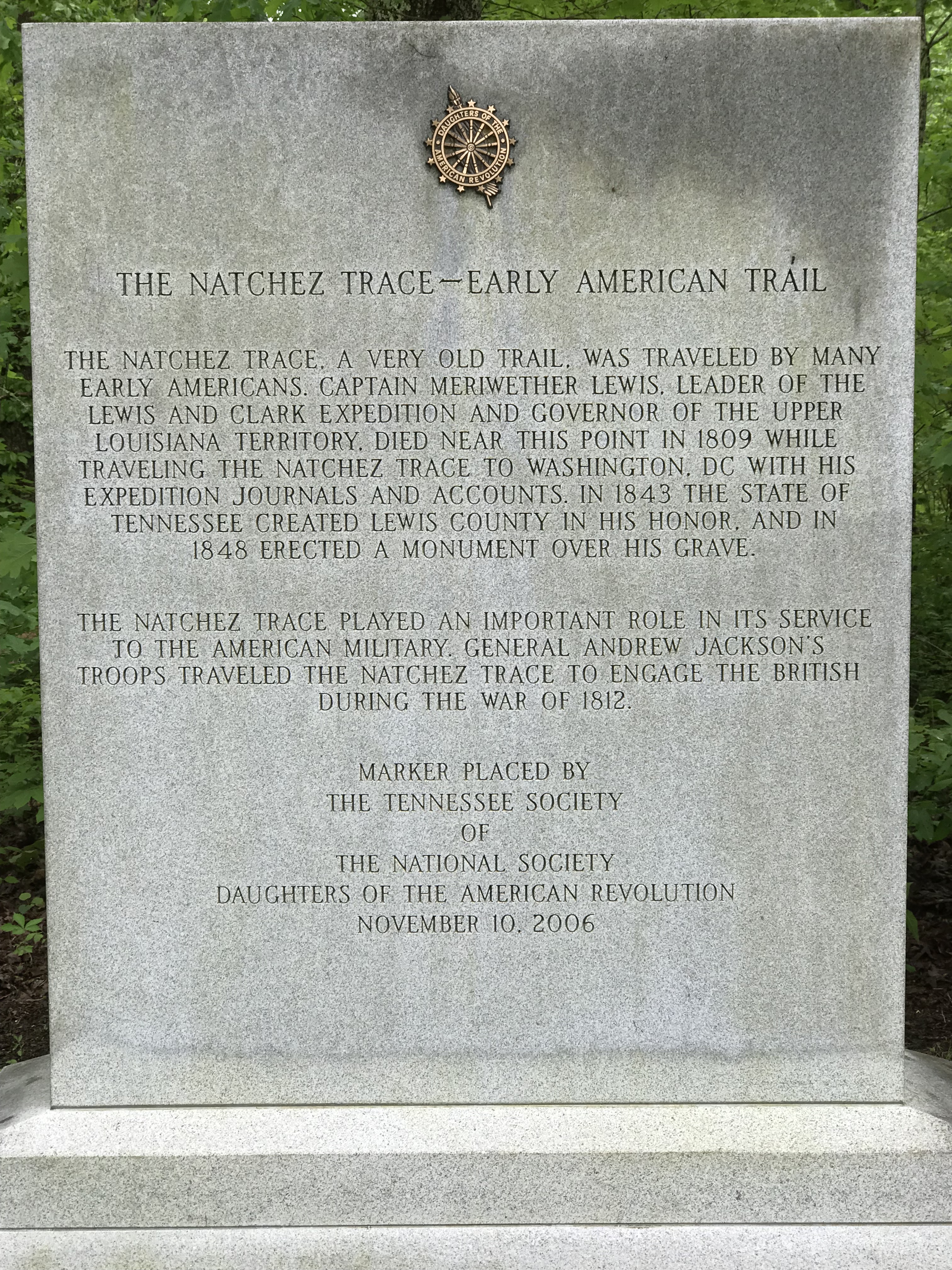

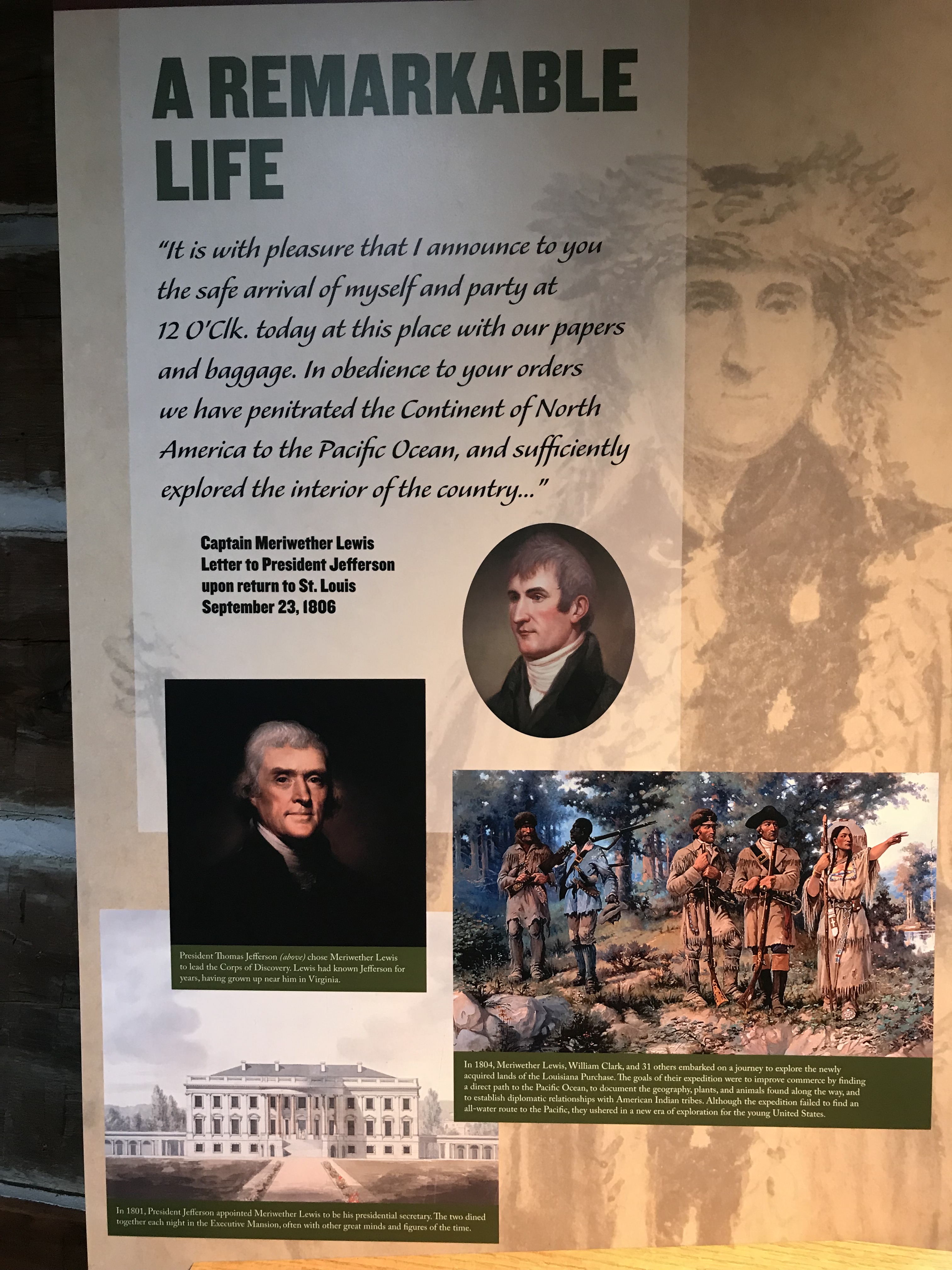

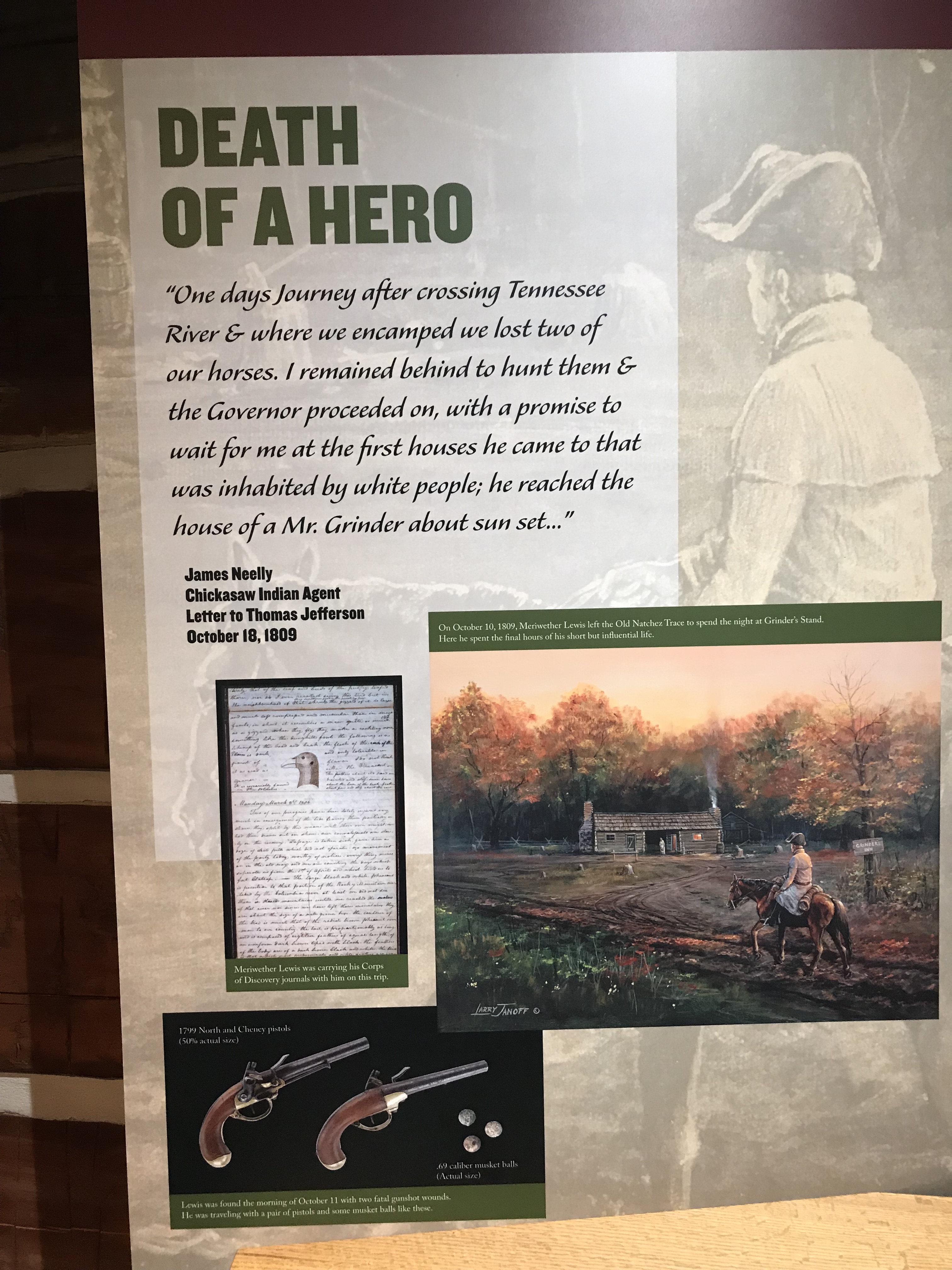

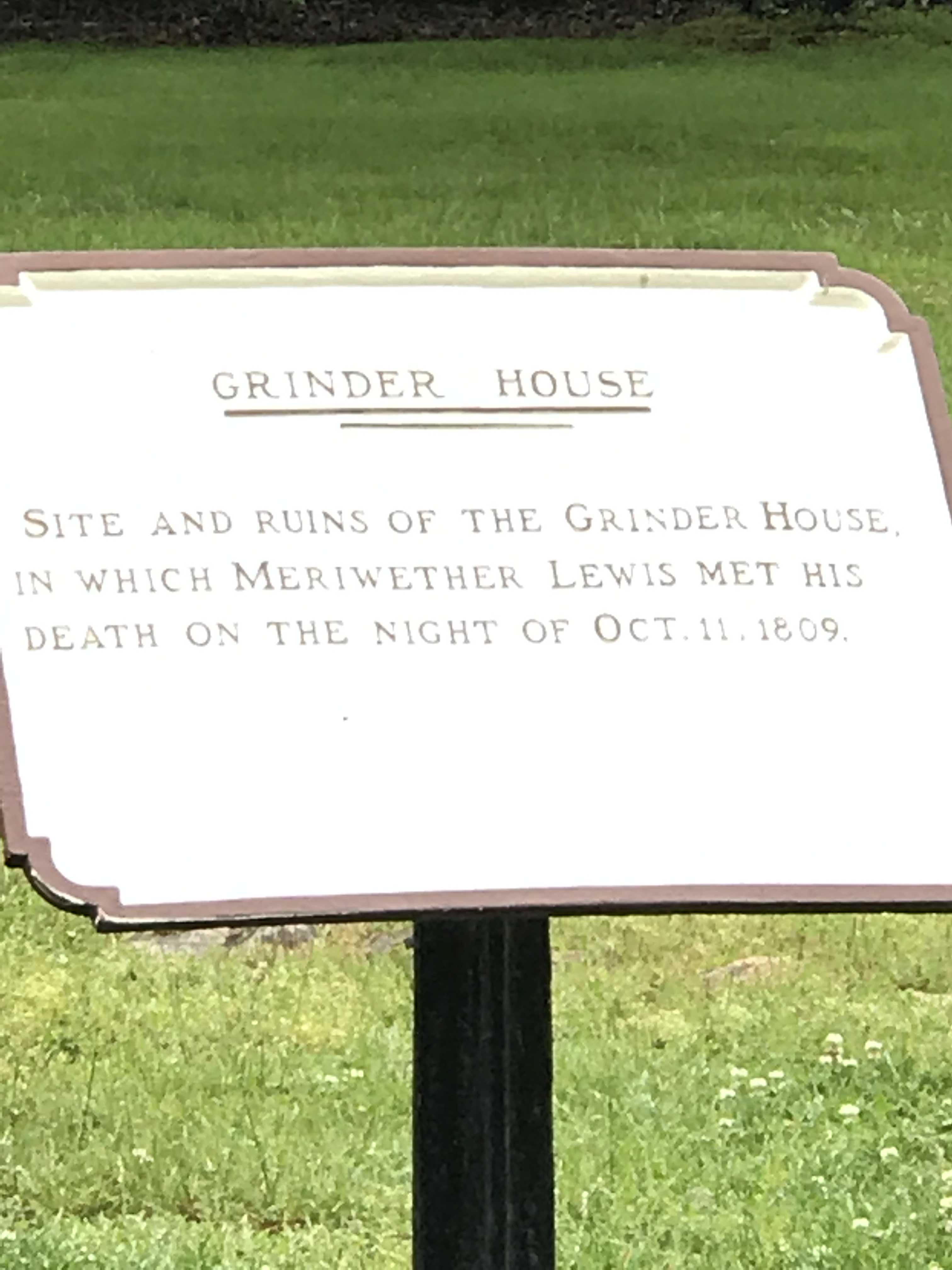

Free camping on The Natchez Trace

Free camping on The Natchez Trace

)

)